Chinese lawyer Liang Xiaojun today tweeted news that Tibetan language advocate Tashi Wangchuk was taken to his family in Trindu county in Kham [CH: Chengduo, Yulshul Prefecture, Qinghai] today after completing a five years prison sentence. He added that it is not entirely clear how ‘free’ Tashi Wangchuk is due to a lack of contact with his family or photographic evidence of his status.

Chinese lawyer Liang Xiaojun today tweeted news that Tibetan language advocate Tashi Wangchuk was taken to his family in Trindu county in Kham [CH: Chengduo, Yulshul Prefecture, Qinghai] today after completing a five years prison sentence. He added that it is not entirely clear how ‘free’ Tashi Wangchuk is due to a lack of contact with his family or photographic evidence of his status.

Tibetans and global Tibet activists expressed concerns for Tashi Wagchuk’s safety and wellbeing, warning his sentence continues with a five-year deprivation of political rights which means that he will not have the rights to “free expression, association, assembly, publication, vote, and to stand in elections” and will see him under constant surveillance.

Tashi Wangchuk, a shopkeeper from Kyegundo in Kham [CH: Yushu County, Qinghai], was arrested in 2016 after he featured in a New York Times report about his plight to seek the right for children in Tibet to learn in Tibetan. The video report highlighted Tashi’s journey from Tibet to Beijing to file a formal complaint about China’s failure to support Tibetans’ right to Tibetan language education.

He was detained on 27 January 2016 and held without trial for two years until he appeared in court on 4 January 2018.

Tashi Wangchuk was charged with the highly politically motivated ‘offence’ of “inciting separatism”, a charge that “criminalize(s) the legitimate exercise of freedom of expression and his defence of cultural rights”, according to UN experts. China’s Constitution states that “All nationalities have the freedom to use and develop their own spoken and written languages.”

Tashi Wangchuk was tortured and suffered extreme inhumane and degrading treatment during the early days of his detention. He was initially held for a lengthy period in a ‘tiger chair’ where he was subjected to arduous interrogation and was repeatedly beaten. His interrogators also threatened to harm his family.

He was denied the right to see his lawyer on multiple occasions during pre and post-trial, in serious violation of his right to a fair trial. On 15 January 2019, Tashi’s lawyer made a request to visit him, but officials at the prison denied this request citing the political and sensitive nature of the case. Most recently, the Chinese authorities blocked Tashi’s access to legal representation on 27 April 2020 and 19 June 2020 with COVID-19 given as the reason for his denied access, despite the fact that there were no reported active cases of COVID-19 in the area. Tashi was not afforded the option of a video call with his lawyer.

Tenzin Tselha of International Tibet Network said: “Today may mark the end of Tashi Wangchuk’s unjust imprisonment, but he remains unfree, with a further five years deprivation of political rights which will see his every action surveilled. Tashi’s only “crime” was to peacefully call for the right of Tibetans to learn in their own language and governments must take strong, assertive action calling for his human rights to be upheld following his release.”

John Jones of Free Tibet said: “We are thrilled with the news of Tashi’s release. He is a Tibetan hero who has shown immense courage and determination. It is an outrage that he was ever jailed in the first place, and it is further galling that he will now have his rights further curtailed and repressed. We vow to continue pushing for his freedom and call on governments to take joint action calling on authorities to immediately lift all restrictions on him.”

Dorjee Tseten of Students for a Free Tibet said: “The fact that Tashi Wangchuk languished behind bars for five years just because of his work to protect the Tibetan language shows just how dire the human rights situation is in occupied Tibet. Many other language rights advocates, like Tashi, are imprisoned in Tibet simply for exercising their rights. This includes 23-year-old monk Sonam Palden, who was arrested after he published a poem about the marginalization of the Tibetan language. We will continue pushing at all levels for Tashi’s rights to be upheld and for the immediate and unconditional release of all other Tibetan political prisoners.”

Tashi Shitsetsang of Tibetan Youth Association Europe said: “Tashi Wangchuk has been criminalised for shedding light on China’s failure to protect the basic human right to education in occupied Tibet. We urge governments to speak out about China’s treatment of Tashi Wangchuk, and all Tibetan human rights defenders, and to press Chinese leaders to stop using the charge of “separatism” to lock up Tibetans who peacefully advocate for their human rights.”

Tashi Wangchuk’s case has been raised by multiple governments and independent human rights experts. In March 2018 six UN human rights experts expressed serious concern over the ruling by a Chinese court to uphold charges of “incitement to separatism” and called for all charges leveled against Tashi Wangchuk to be dropped. In January 2018, government delegations from the UK, EU, US, Germany, and Canada attempted to attend the trial but were all denied access. Court officials also refused to allow a New York Times reporter into the trial, despite several requests.

China is replacing Tibetan-language schooling with Chinese and coercing parents to send children to faraway residential schools. This insidious plan has been designed to stamp out the next generation of Tibetan speakers and in an attempt to eliminate the Tibetan identity.

China describes the language policies for occupied Tibet as “bilingual education,” but with Tibetan-language schools being forced to close their doors and kindergarten-aged children being forced to learn almost only in Chinese, it’s clear that this is a deliberate effort to strip Tibetans’ language and culture from them.

Tibetans have expressed widespread concern about the increased crackdown on Tibetan language rights, which is resulting in a loss of fluency among the younger generation. A new urgent action, launched on 18 January, calls on Chinese leaders Vice Premier, Sun Chunlan and Minister of Education, Chen Baosheng to immediately reinstate Tibetan language education, and make it available to all Tibetan students at each stage of their education.

Continue reading → Respected Tibetan monk Khenpo Kartse released from prison at end of sentence

Respected Tibetan monk Khenpo Kartse released from prison at end of sentence

Report by ON JULY 18, 2016

Khenpo Kartse, the popular and respected religious teacher whose detention in 2013 sparked peaceful protests and a silent prayer vigil, has been released after serving two and a half years in prison.

Khenpo Kartse, whose case became prominent internationally with calls for his release by governments and thousands of Tibet supporters worldwide who petitioned on his behalf, issued a low-key social media posting in Tibetan on following his release in the form of a short poem. In the poem, he said he was moved by the concern that had been demonstrated towards him.

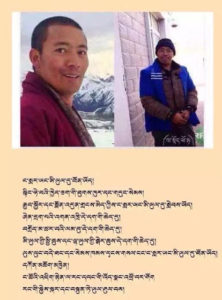

The detention of Khenpo Kartse caused widespread distress, with hundreds of Tibetans gathering peacefully to protest his arrest, and a rare silent vigil on his behalf being held outside the prison in 2014.[1] An image of Khenpo Kartse (Khenpo means abbot and Kartse is the shortened form of his name, Karma Tsewang) handcuffed and in prison uniform circulated on Chinese social media following his initial detention.

Khenpo Kartse, an abbot from Gongya monastery in Nangchen, Yulshul (Yushu) Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture in Qinghai, is well-known for his environmental activism and support for the preservation of the Tibetan language and culture. He was active in social work following the devastating Yushu earthquake in 2010. He was detained on December 6, 2013[2] in the provincial capital of Sichuan, Chengdu, and taken to Chamdo (Qamdo or Changdu), where he was apparently sentenced behind closed doors. There was concern for his health in custody as medical problems that were known before his detention went untreated, he was kept in a cold cell and had inadequate food.

Full details are not available about the circumstances or exact date of his release, nor of the exact charges against him, but reports circulating on social media indicated that early reports of a two and a half year sentence were correct. Details about his current health condition are not known, and he is likely to be under very close supervision by the Chinese authorities.

Typically, former prisoners face profound fear and anxiety upon their release, combined with a constant awareness of being under surveillance. Their psychological suffering is often heightened by the knowledge that their family and friends are also under pressure from the authorities. They often suffer from severe financial hardship as they are dependent on their families, often unable to find work due to their status as a former political prisoner. Monks and nuns are not permitted to return to their monasteries or nunneries. Sometimes they cannot afford medical treatment needed following severe torture or years of poor nutrition in prison.

Because they are perceived by the authorities as a threat to the Party-state as a result of the views and actions that led to their sentencing, former prisoners are strictly controlled and isolated, partly in order to create a visible deterrent to other Tibetans who may seek to express views that are counter to those of the Beijing leadership, or those like Khenpo Kartse, who are active in the community and wider society.

Khenpo Kartse’s Chinese lawyer Tang Tianhao traveled several times to Chamdo and was only allowed to meet with him twice, for a short time, according to Radio Free Asia and other sources. Tang Tianhao was later compelled to withdraw from the case due to pressure from the authorities. Following his initial detention, the lawyer was told by Chamdo police that the case involved endangering state security, according to Beijing-based Tibetan writer Tsering Woeser.

Khenpo Kartse’s imprisonment attracted significant international attention, as well as expressions of solidarity and brave vigils by Tibetans in Tibet. Thousands of ICT supporters across the world added their names to petitions for his release and his case was raised by several governments in dialogues on human rights with China.

A Facebook posting on July 15 written by Shiwapa Kunkyab Pasang welcomed Kartse’s release and expressed gratitude “to all who support justice by standing behind oppressed Tibetans in Tibet, including all political prisoners.”[3]

The following poem by Khenpo Kartse appeared in an undated post since his release, translated from Tibetan into English by ICT below.

I am back once more in the human world,

Due to the immeasurable concern, sympathy, support, and well-wishes of you dear ones,

I am back once more in the human world

For the duties that come with strong attachments,

For the paths we have yet to take,

For the common welfare of the human world, and individual aims for the divine,

Healthy in body and sound in mind, I am back once more in the human world

All-knowing Three Jewels,

May the light of freedom shine in our world!

By the one from Yushu, on the occasion of his own birthday

Footnotes:

[1] ICT report, October 22, 2014, https://www.savetibet.org/popular-religious-teacher-khenpo-kartse-sentenced/ Also see:https://www.savetibet.org/rare-vigil-outside-prison-to-support-popular-tibetan-monk/

[2] Some sources say he was detained on December 7, 2013.

[3] Radio Free Asia report, July 7, 2016, Tibetan Religious Leader is Freed From Prison After Sentence Ends’

Read more about Khenpo Kartse’s case

Continue reading →Orignal post by Phayul, 7 June 2014

Chinese authorities in Lithang have prevented local Tibetans from holding a prayer for the long life and welfare of jailed Tibetan spiritual leader Tulku Tenzin Delek on June 2.

Tibetans including monks and laypeople have come together at the Nalanda Theckchen Janghub Choeling for the prayers but were stopped an rebuked by local Chinese authorities.

A Tibetan source said that the Nyagchu County officials have directed the local authorities to stop the prayer for the Tibetan lama jailed on charges related to a series of bombblasts in Kardze. Tulku Tenzin Delek, however, denies all the charges against him saying he had been framed on false allegations by the authorities, and appealed supporters to continue their fight for his release.

Disciples of Tulku Tenzin Delek have also been renovating Tulku’s residential quarters at the monastery but were also asked to stop work. The source said all the local Tibetans including Tulku’s disciples are waiting optimistically to the release of Tulku Tenzin Delek. Exile Tibetans lead by disciples of Tulku have also launched a campaign for his release.

Meanwhile, four Tibetans have been arrested on April 28 but later released after seven days in detention without charges. Akal Dorjee, Ngawang Lobsang, Apha Norbu and Jhangshar Kombey were stopped on their way to the County headquarters to submit a petition calling for the release of Tulku Tenzin Delek, who is serving a life sentence in a Chinese prison.

The four were detained for seven days and released on May 4.

Continue reading →A report by Wall Street Journal – See original post

BEIJING—When European and Chinese diplomats met last year for their annual, often fraught discussion on human rights, the European Union side presented a list of Chinese political prisoners whose cases it thought should be reviewed, as it had done at previous meetings. But this time, the Chinese refused to accept it.

It was a blunt loss of face for the EU diplomats, people familiar with the event said, and illustrated a hardening of China’s position on human rights and the diplomacy around it.

Chinese officials have mostly stopped accepting long lists of its prisoners from foreign advocates of their release, said John Kamm, a businessman-turned-human-rights activist. Even when they do, Western diplomats say, Chinese officials often don’t provide information on the cases, much less release the prisoners. The Chinese foreign ministry didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment on its policy regarding the lists.

Twenty-five years after the Chinese military quashed democracy protests in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, a confident Chinese leadership, bolstered by years of robust economic growth, continues to tightly restrict civil liberties with little concern for the disdain of outsiders. The human rights diplomacy that emerged post-crackdown, human rights activists say, is effectively defunct as Beijing sees less need to negotiate with foreign governments over how it treats its own citizens.

Aside from ignoring or flat-out rejecting the lists, Beijing has also suspended many of the annual dialogues on human-rights issues that it held separately with nine governments, according to the diplomats and human-rights researchers. The ones that haven’t been called off, they say, are those with the U.S., the EU and Australia.

In April, Beijing canceled a recently agreed-upon plan with Britain to revive their dormant human-rights dialogue, after the U.K. labeled China as a “country of concern” in its annual report over a range of issues including police torture and restrictions on speech. Chinese foreign ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying slammed Britain for “rudely slandering and criticizing China’s human-rights situation.”

The U.K. supported a call by nongovernmental organizations to stage a moment of silence at the United Nations Human Rights Commission for Cao Shunli, an activist who died in detention in China. That also fed Beijing’s pique, diplomats said. China’s foreign ministry later criticized what it saw as “mistaken” remarks about Ms. Cao’s case. ”

She received conscientious and proactive treatment during her illness and her legal rights were ensured,” a spokesman for the ministry said.

China has so far refused to schedule this year’s rights dialogue with the U.S., which usually takes place in the summer, according to several people with knowledge of the situation. President Obama angered Beijing by meeting with the exiled Tibetan leader theDalai Lama in February, and the government’s displeasure was compounded by the recent indictments of five Chinese soldiers on charges of cybertheft.

China’s foreign ministry declined to comment on the dialogue. China’s refusal to engage on human rights has real consequences, according to diplomats, rights groups and dissidents. Former prisoners say the foreign lobbying tends to get them better treatment.

Ni Yulan, a lawyer jailed multiple times for protesting forced housing evictions, uses a wheelchair as a result of a beating she suffered while in detention. Police in China have declined to comment on Ms. Ni’s detention and the allegation she was beaten.

Inquiries from the U.S. Embassy, Ms. Ni said, led officials at the Beijing Women’s Prison to provide her with a bed while she was detained in 2009. Previously, she said, she had been forced to sleep on the ground.

“Because of their help, the conditions of my imprisonment improved greatly,” says Ms. Ni. “I’m deeply thankful for the support of foreign diplomats.”

The practice of submitting prisoner lists grew out of the aftermath of military assault on June 3 and 4, 1989, to dislodge protesters from Tiananmen Square, and the suppression of demonstrations elsewhere. Hundreds were killed, though a precise number of dead isn’t known. More than 1,500 were imprisoned nationwide.

Western governments, under pressure from outraged citizens, were looking for ways to put human rights on the agenda when they re-engaged with Beijing. Chinese leaders were anxious to end months of being treated as a pariah, and fearful of scaring off foreign investors and derailing the overhaul of its centrally planned economy. Prisoner lists provided a solution. The first such list was submitted ahead of then Secretary of State James Baker’s visit to Beijing in 1991.

Lorne Craner, who served as an Assistant U.S. Secretary of State under George W. Bush, remembers submitting a list of more than 90 names ahead of the U.S.-China human rights dialogue in 2001. Roughly a dozen were later released, including Tibetan nun Ngawang Sangdrol, set free in 2002 after 12 years in prison for advocating Tibetan independence, and Rebiya Kadeer, an activist for the mostly Muslim Uighur minority, who was released in 2005.

“The Chinese would say the releases were unrelated to the lists and I respect that,” Mr. Craner said. “But the fact was that a fair number—I was told a record number—of people on the lists we handed over were getting out.”

As the world’s second largest economy and the biggest trading nation, China can count on economic issues factoring into relations with Western governments, many of which have continued to criticize Beijing for its curbs on free speech and its jailing of political critics, religious activists and campaigners for the rights of Tibetans and Uighurs.

Chinese leaders reject pressure on human rights “because they can, and because there’s no particular penalty for them in doing so,” said Sophie Richardson of Human Rights Watch. “It’s not, for example, that the British government is going to take something off the table that China wants in response to the human-rights dialogue being suspended.”

China’s weathering of the global financial crisis on top of Beijing’s opulent and widely praised Summer Olympics in 2008 persuaded Chinese leaders that their model was superior, according to diplomats and some analysts. Mr. Kamm, the rights advocate, said he was told that a policy decision was made in 2012 to no longer accept prisoner lists “either in the run-up to or during” human rights dialogues.

The rights dialogues, when held, have become increasingly stilted and marginalized, say the diplomats who take part in them. China’s foreign ministry has taken to holding them in far-flung locales, away from the scrutiny of activists and journalists. Last year’s EU dialogue was held in Guizhou, one of China’s poorest provinces, and the last U.S. dialogue, in July, took place in the southwestern city of Kunming.

Continue reading →